Tactical urbanism, new urbanism, sustainable urbanism, circular urbanism, DIY urbanism, collaborative urbanism, landscape urbanism, re-urbanism… There are a thousand urbanisms! What lies behind these -ism names? And what is urbanism, at the end of the day?

Cities offer a lot of opportunities, but they also concentrate many environmental, societal and economic challenges. Since the age of the industrial revolution, problems such as gentrification, urban sprawl, shortage of housing, insecurity, social inequity, pollution, the scarcity of natural resources, etc. have appeared in cities. A lot of these problems remain unsolved, while many more are appearing. Urbanism, as the field that studies urbanization and the urban environment, seems to be ineffective at solving contemporary problems. Why?

The problems facing cities are “wicked problems”

First of all, cities cope with problems of great complexity, with multiple variables. For that reason, Rittel and Webber (1973) say that urban problems are “wicked” and have no standardized solution. In fact, it is impossible to treat one problem (for example, fighting the shortage of housing with the construction of new apartment buildings) without systematically creating new problems elsewhere in the city or in the world (the rise of renting prices for example, the destruction of agricultural land, the impermeabilization of the ground…). Causes and issues are closely interrelated, which requires a more systemic, global approach to solving urban challenges.

There is no clear definition of what urbanism is

As the problems in cities are multiplying, urbanism as a field of study and practice is gaining a lot of attention. However, there is no clear, universal description of what urbanism is. From what I have gathered during my studies, urbanism is a combination of 3 things:

- It is the study of cities and their geography, economy, politics, sociology and culture, as well as the impact of these forces on the built environment;

- It is a field of practice, with the planning and development of cities and towns;

- It is the way of life which is typical to any town, city or settlement.

There are hundreds of urbanisms

Adding to this, urbanism comes in many flavours. There are literally hundreds of typologies of urbanism (not all of them scientifically acknowledged), all of which have emerged as an attempt to improve cities. During our Master in Urbanism Studies (at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm), my colleague and friend Vasilis had counted 294 theories about urbanism (there might even be more at this date) which you can find all mentioned in his master thesis, Urbanism in the making: A handbook of survival. There would be no point in describing them all; however, I find interesting to identify the dominant trends behind these many approaches.

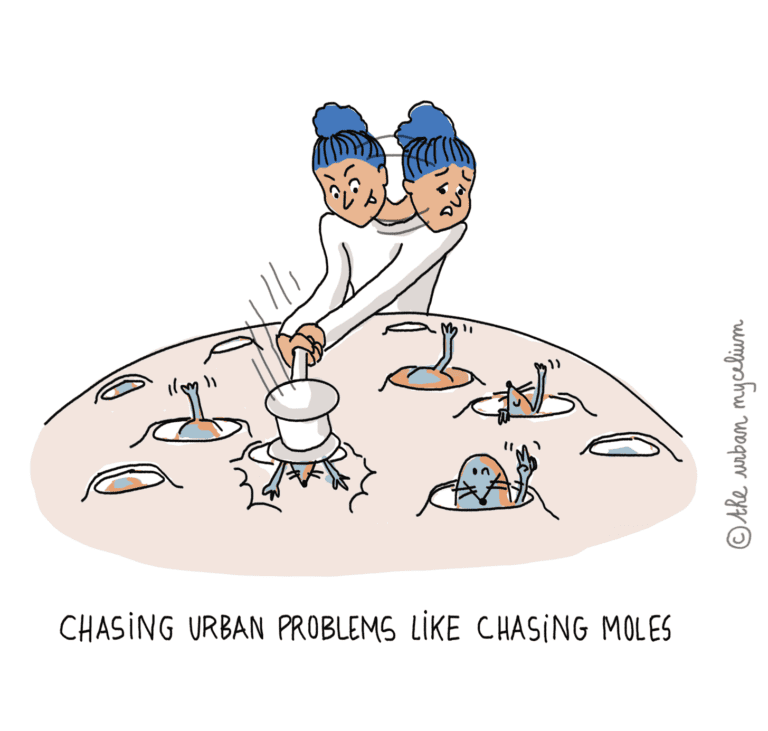

This task has been carried out by different people in academia and practice, including Haas and Olsson (2013). They came up with 5 different categories:

- New urbanism / traditional urbanism: urbanisms that advocate for some sort of a return to the past, using vernacular development, human scale and city at eye level planning

- Re-urbanism: urbanisms that rebuild the city on itself, with regeneration strategies to fight back sprawl and modernist urban development

- Post-urbanism: urbanisms that look beyond the present, with urban development organized around money flows, business quarters, high-tech and progress as ideals

- Everyday urbanism: bottom-up urbanisms organized around community planning, with participatory approaches (activism urbanism, placemaking, DIY urbanism, tactical urbanism, etc.)

- Sustainable urbanism / green urbanism: urbanisms that focus on the (re)introduction of nature in cities and integrate biophilia, agriculture, ecology, landscape, climate change adaptation strategies, etc. with approaches that are either low-tech or high-tech

Based on their work, I have drawn the following figure, mapping the main movements in the branding quest for better cities. I should mention that the place where the different theories are mapped is a result of my own personal interpretation (meaning that it shouldn’t be taken as scientific evidence but more as a start for discussion).

The interesting point to me in that discussion, is the link between the evolution of urbanism and the one of humankind. Just like Little Thumbling with his pebbles, these 50 shades of urbanism mark the concerns that humans have had at a certain point in time, like landmarks on the path of human evolution. Taken together, these theories provide an interesting picture of society and people’s quest for a better world. Of course, I am wondering which theory will be the next…

Because there will be new ones for sure. When cities haven’t been discussed from a certain perspective or when a specific topic wasn’t given enough attention, then a new theory about urbanism appears. Right now for example, current trends include digital urbanisms and even more pandemic urbanisms (although the latter is probably too early to discuss). This never-ending city branding phenomenon is problematic, Vasilis says in his research paper, for the following reasons:

- First of all, these urbanism models are not always created with the idea of common good, but sometimes as a way to draw attention to their owner’s profession or works;

- Secondly, these models are all created as a form of dissatisfaction with the previous ones, which is very problematic as it prevents the emergence of co-creative and generative solutions;

- Adding to this, new typologies of urbanism are often presented as the final, “best” model that overwrites former models; as a static solution which leaves little room for versatile problem-solving.

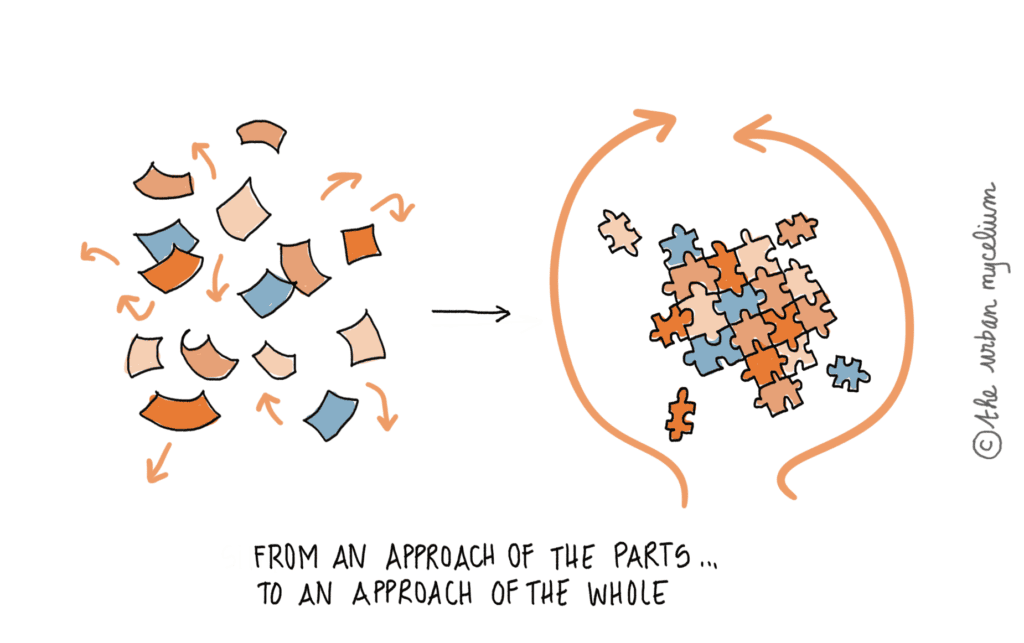

As a consequence, urbanism has become a very fragmented discipline, that has lost its coherence over time as well as its strength and most likely, legitimacy. What Katrina Johnston Zimmerman brilliantly calls “the blessing and curse of branding urbanism — something for everyone, but not everyone for one thing”.

Towards a coherent urbanism in the making

For all of the reasons above, urbanism more often than not struggles to solve contemporary problems in cities. So, what to do, then?

- Urbanism is a process that involves change: the approaches to city making must include that notion of evolution;

- More cooperation and cross-sector innovation are required between stakeholders from these multiple urbanisms (i.e., between practice and academia, between urban professions, between different urbanism approaches) but also with other disciplines outside of urbanism;

- All typologies of urbanism are valuable and have to be discussed, but we shouldn’t forget the big picture. The many approaches can actually co-exist while being encompassed in a larger core of reference dedicated to improve cities.

Urbanism has constantly evolved through time, as demonstrated by the multitude of urbanism theories, and will continue to do so. What seems to be emerging, though, is a more systemic, co-creative approach to cities that includes all of those urbanisms and many more, while being geared towards a higher, evolutionary purpose.

As the world is becoming more and more urban, so is everything. There is little if nothing anymore that is not affected by some product of urbanization. That makes it even more important to discuss inclusion and cooperation in urbanism: something that has a place for everyone and for everything to be discussed.

Barnett, J., 2011. A Short Guide to 60 of the Newest Urbanisms. Planning Chicago, 77, 4: 19-21.

Haas, T. and Olsson, K., 2014. Transmutation and reinvention of public spaces through ideals of urban planning and design. Space and Culture 2014, Vol. 17(1) 59–68, Space and Culture Journal, Sage UK.

Ingvar Raptis, V., 2017. Urbanism in the making: A handbook of survival. KTH, School of Architecture and the Built Environment (ABE), Urban Planning and Environment, Urban and Regional Studies (Urbanism studies).

Rittel, H.W.J., Webber, M.M., 1973. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Policy Sciences, 4:2 p.155