Have you ever found yourself in a situation where you were in the middle of talking to someone and you suddenly felt an urge to use the restrooms? Do you remember having troubles to follow the conversation perhaps? And you focus on your bladder instead?

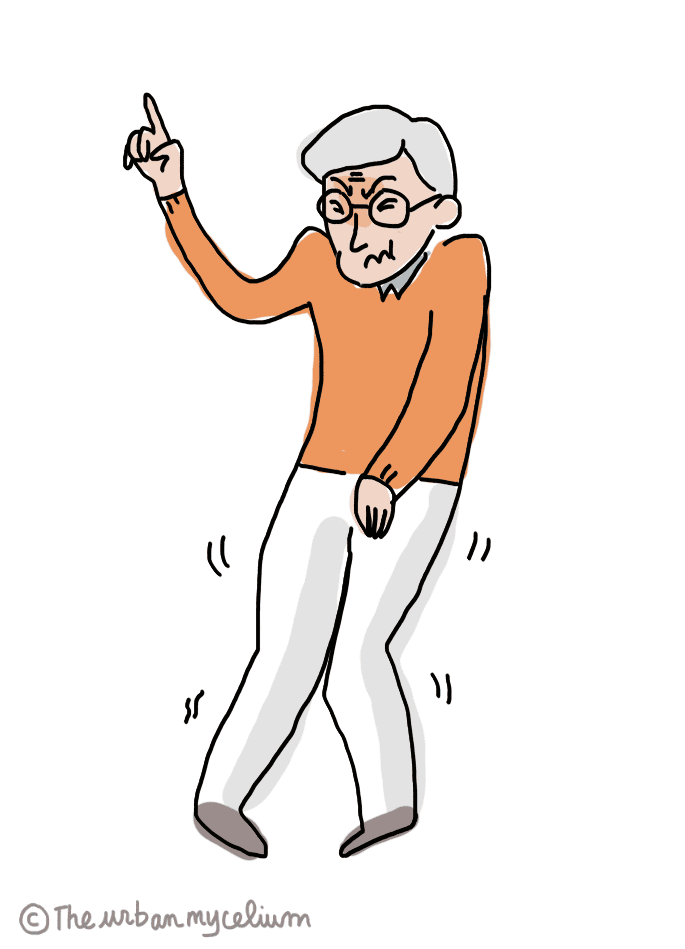

Well, this is kind of what happens at the start of a public participation process for an urban project. Imagine you are a municipality or a property developer. Let’s say a social housing company who would like to renovate ageing apartment buildings, with the input of the tenants. You want to invite the residents to a public meeting or a workshop, in order to brainstorm improvements for the residence. The very first time when you will meet people, you can safely bet that they will almost all come with a strong urge to pee. That they will be focused on their bladder, more than on the renovation of your residence.

To be fair, there is quite a big problem with the timeline of urban development projects. Participating in public participation programmes for an urban project, that will be inaugurated in only 10 or 15 years from now, is quite frustrating. It is already not easy for urban practitioners, who have to deal with multiple constraints and unexpected problems. But it is even harder for future inhabitants and users. People are OK to participate in imagining the city of tomorrow, but what they mostly want is concrete and immediate changes in their daily lives.

Because for them, what matters is the everyday, with its share of joys and sorrows. The residents’ “pressing” desires are the hole in the pavement down in the street, the lamppost that has been broken for 2 months, or the dog poop that is never picked up in front of the building’s entrance.

But how do we avoid frustration? Well, if we could respond to simple requests faster, that would already be amazing.

Don’t underestimate the pebbles in people’s shoes

Here I will share 2 simple but effective ideas, which have proven efficient several times in the urban projects that I have managed. Three steps that will help you make the participants feel relieved while generating real added value for the project on the long term.

- Start by conducting a diagnosis of the everyday life of the inhabitants, residents or users concerned by the building / urban project. Collect the small joys but also everything that they find irritating or itchy, from the hole in the road to the broken elevator. This phase in itself is very powerful!

- First of all, it will allow people to empty the problems of their bladder, and to be more focused for the rest of the discussion on the urban project itself. If you skip that, you will for sure hear again and again about that hole in the road!

- Secondly, this step leads to the co-construction of an interesting portrait of the neighbourhood or building, from the point of view of the users. It raises awareness about what works and what doesn’t. A qualitative diagnosis, which usually is a great complement to the more technical site analysis made by the planning professionals.

- Then, make a commitment to take corrective actions and to keep people informed about the changes. At the very least, provide clear explanations at the next meeting about why X is possible and Y isn’t. In general, people prefer a “no, we can’t do that because…” than no answer at all. As a project contractor, this also allows you to communicate on the implementation of first concrete actions, without waiting for the delivery date of the building, public space or neighbourhood! And by taking care of the pebbles in people’s shoes now, without waiting for the construction works to start, you help create a climate of trust with the participants. This is where a relationship of true cooperation can be established between the power holders and the citizens.

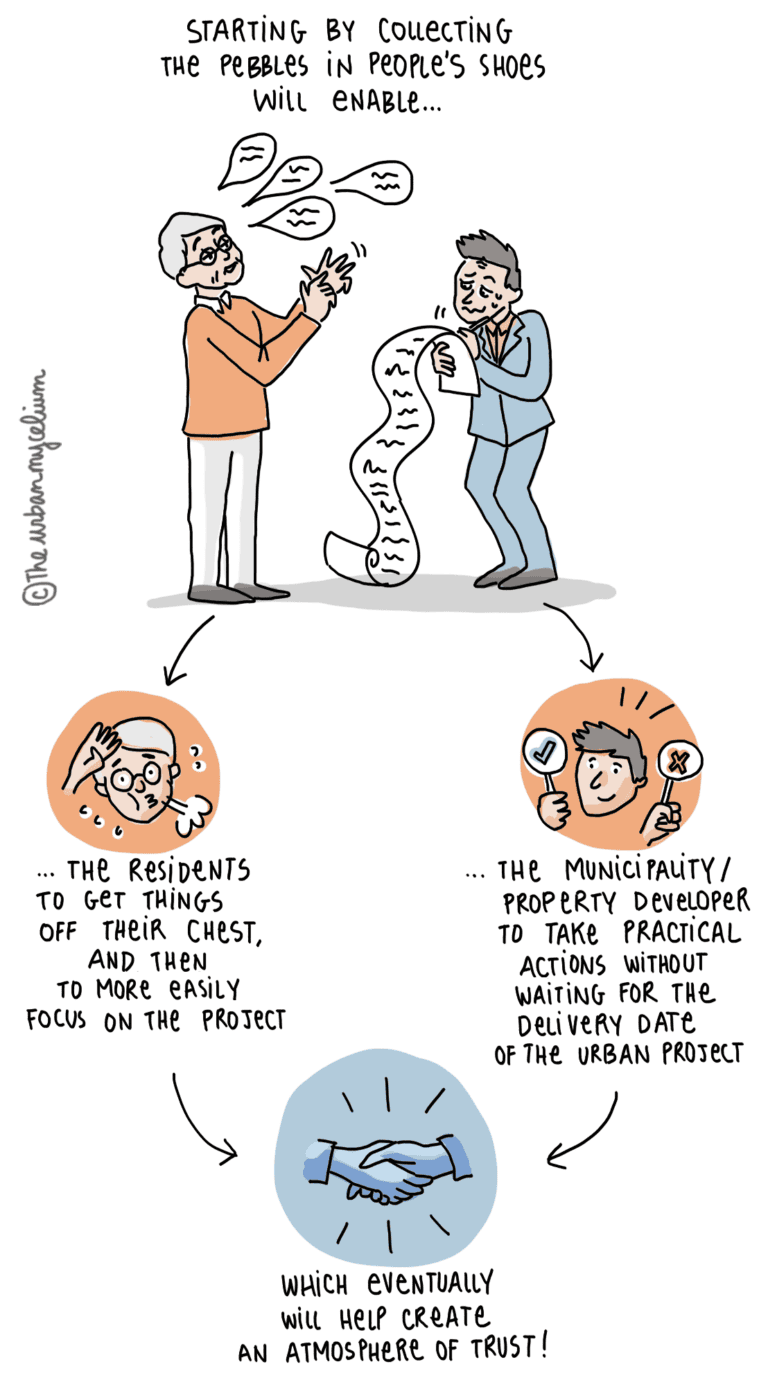

You immediately feel better, once you have relieved your bladder, right? After the everyday problems have been dealt with, we can move on to the ideation phase with more confidence and relevance. At the end of the brainstorming, when you have collected proposals to improve the building / urban project, it’s time to prioritize ideas depending on their added value for the local area and on how easy they are to be implemented. To prioritize ideas, you can use the apple tree metaphor, as displayed in the matrix below:

- Low-hanging apples. Also called the “quick wins” by my peers and friends at STIPO, these are the ideas that are easy to implement and that immediately make a difference in the daily life of residents, without too much risk for the project contractor. Start with these!

- Apples in the sky. Hard to catch, but delicious, these are ideas that have a strong impact on the long term, but require more effort than the quick wins. Use these ideas to fuel your long-term strategy.

- Apples that have fallen on the ground. These actions are easy to implement but have little impact on the project. You can leave them and prefer the previous two types of actions, or else implement them if you have time and resources left.

- Wormy apples. These are the false good ideas, the proposals which bring little added value to the project, all while being resource intensive. Make sure to avoid those!

How might you use the apple tree matrix?

A good way to go would be to launch concrete short-term actions while building a solid long-term strategy for the neighbourhood or building.

- Target first the “quick wins”, which are essential in making a difference in people’s lives and building trust. Although theses short-term actions are less visible and marketable, they pave the way for working differently with the inhabitants.

- However, do not forget the structural changes that you want to implement in the long term. Without that, the “quick wins” would only be window dressing!