There is a growing recognition that the making of the city should not be reserved to the experts only. After decades of exclusion, residents and users of the city finally start to be more and more involved. However, the involvement of different stakeholders in urban planning and design brings its very own share of questions. Is public participation for everyone? Who are the ones who actually participate? What about those who don’t?

The public and private actors of the city who organize participatory processes often would like everyone to participate. By everyone, they mean a great number of people, but also people with different cultures and situations.

Unfortunately, not everyone participates in collaborative city making. Even with creative means of communication and tactics such as free food or concerts, current participatory processes often fail to attract people whose voice is heard the least. Parents of young children, single mothers, low-income people, people working at night, the homeless, racialized people, gender minorities, kids and teenagers, students… they rarely make it.

Whatever you do, it is always the same people who participate

No matter how hard we try, participatory processes always end up attracting the same kind of participants: mostly white, non-disabled, heterosexual men, aged 50 – 75, usually with education and from the middle or the upper class.

A first category of participants are people with leadership, who have or previously had jobs with responsibilities. They will usually not hesitate to voice their opinion and will be willing to share their extensive knowledge with others.

But in most cases, participants are people who come to defend their own private interests: for example, the value of their house or apartment, the calm of their neighbourhood, etc. Anything that they might see as threatened by the construction of the future urban project.

Although their concerns are very understandable, this pattern raises a real issue. The more the public debate will be monopolized by the few – who happen to know exactly how to make themselves heard, the more we’ll give credit to defensive strategies that are not geared towards the interest of all.

Not everybody is focused on their personal interest, though. There is actually a third category of participants. Either environmental activists, supporters of cycling, or strong advocates of the human scale, these usually younger participants are already involved in some form of civic engagement. They typically have strong societal values which they won’t hesitate to fight for. Quite often, these participants end up dropping at some point, because they already have many other commitments: the parents association at school, an environmental organization or a sports club, etc.

Of course, I am exaggerating on purpose. But beyond these stereotypes, there is a painful truth. The one that today’s participatory processes tend to be confiscated by privileged people, who feel legitimate and have enough time and resources to attend. And this is problematic, because this means that the participatory democracy that we strive so much for is no longer “participatory”.

Towards a more inclusive and representative participation

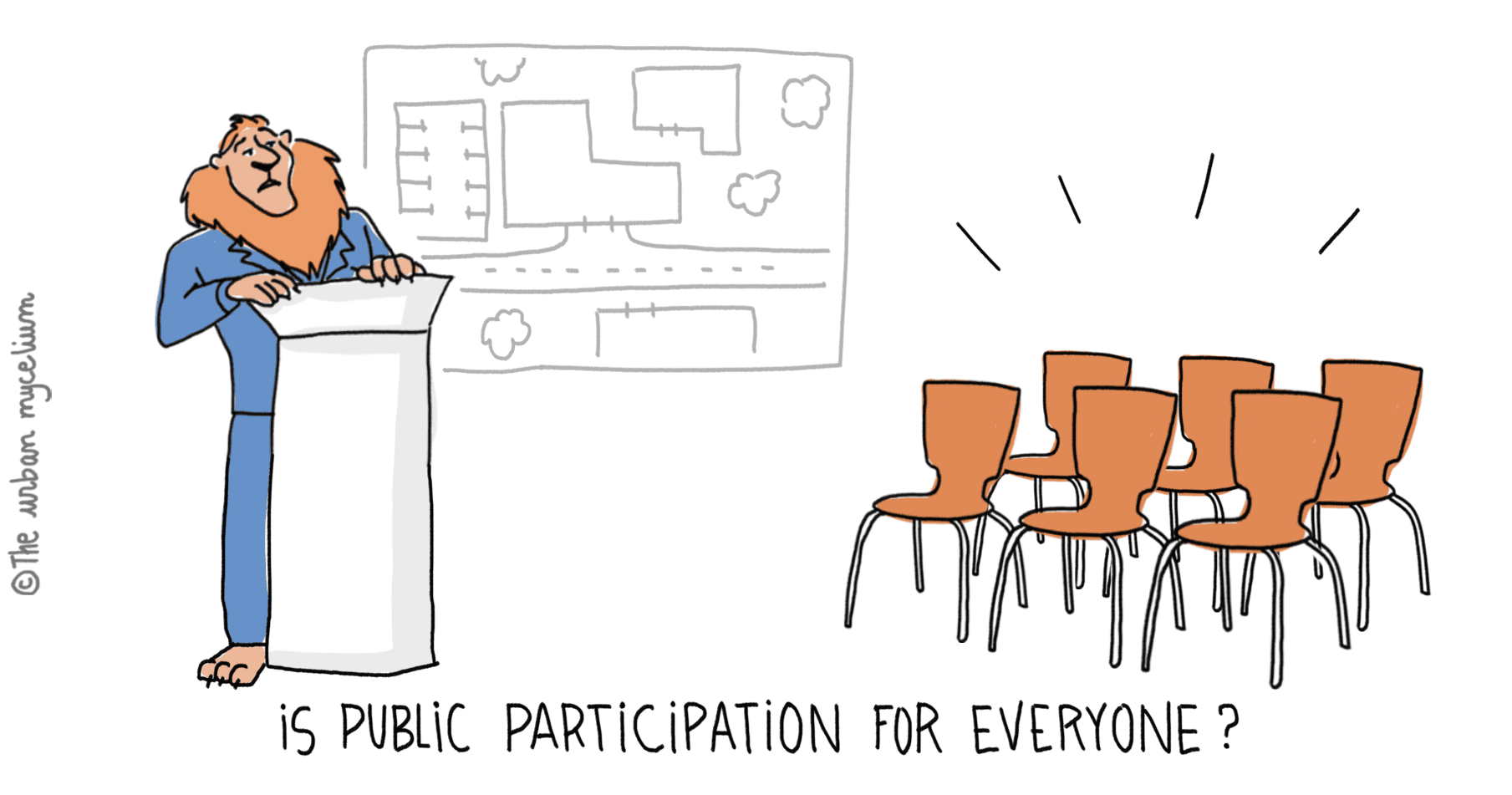

So, what should we do in order to be more inclusive and attract crowds beyond the usual suspects? Here are a few options to consider.

- Restrictions: using rules to increase the attendance of those whose voice is heard the least

- Random drawing: in most cases, participation is voluntary. In order to have a more diverse panel, selecting people randomly from a list (register of voters, a list of tenants, etc.) could be an option. Of course, there should first be a serious discussion about the selection criteria, together with the power holders. This principle was used for example for the Citizens Convention for the Climate, held in France in 2019-20.

- Mixed meetings: this is about creating safe spaces in which people facing a similar situation can feel free and comfortable enough to share (this is for example the concept of Alcoholics Anonymous). Depending on the project, there could be meetings for marginalized people (women-only workshops, workshops for non-heterosexuals, etc.).

- Enforcing a Public Participation Day at work: just like there is a Defence and Citizenship Day in France (a compulsory one-day program for young people on citizenship and defence), or a Solidarity Day for companies of the private sector (a day of work intended to fund actions for the elderly or the disabled), there could be a Public Participation Day when employees have to engage in city making activities.

- Enabling: increasing means to rise public participation

- Online participation: in recent years and especially since the pandemic has started, new technologies have hit the market of public participation. Online participatory platforms, virtual workshops, participatory budgeting, the social media… help reach a greater amount of people, especially younger people who are familiar to such means of communication.

- Diversifying the formats of in-person participation: when talking about public participation, we often picture group workshops in the municipal hall. Actually, there are other ways to collaborate with the users, which don’t require them to move to the power holders. Let’s move to them instead! Interviews at people’s homes or exploration visits on site for example are alternative options that may better suit them.

- Breaking down the physical barriers to public participation

For many people, participating in public debates requires to take a day off or to find a babysitter. In order to make their participation easier, one can provide babysitting at the venue, for example; or offer different times for the meeting, or organize the event not in the city centre but in the neighbourhoods that are further away.

- Incentivisation: rewarding the ones who participate or making public participation desirable

- Rewarding can be a good way to encourage certain behaviours. Countries like Italy, France or Spain offer their citizens subsidies up to 500€ to buy new electric bikes, as a way to encourage cycling and to cut carbon emissions. The same logic may be used to rise public participation on city making projects.

- Creating expectation: from fun activities (for example free food or music concerts at the venue) to inviting star speakers, there are many ways to making public participation desirable.

And you, what are your tips to increase community engagement and make public participation more inclusive? Let me know!

In any case, the participatory trend opens up a can full of questions around the topics of inclusivity and representativeness. We have some work ahead of us before we make public participation really inclusive and efficient at involving the ones whose voice is heard the least. But whatever the strategies, is it possible to escape this recurring pattern? Should everyone actually participate? Keep in touch, we’ll try to answer in our next article!