In recent years, we have observed a growing number of participatory democratic mechanisms in cities. Participatory budgets, consultation workshops, or citizen committees are different approaches that all aim to involve citizens in the making of the city. Even the political programmes during the last French municipal elections demonstrated a growing concern around “citizen participation”. However, the objectives behind the politics of participation are not always clear. Why do more and more city stakeholders refer to these participatory processes? For what reasons?

In the last few years, I have been involved in more than a dozen participatory urban projects, contracted by actors such as municipalities, real estate companies, urban planners, and social housing corporations. Most often, we noted that the root intention behind the participatory approach was not clear for the decision makers. Of course, they had a concrete aim in mind, for example designing the new neighbourhood together with the local community, or creating a shared housing group in an apartment building. But most often there had been no deep discussion beyond these goals, especially regarding:

- The agenda behind the politics of participation (why do we really want public participation, for what purpose? What root problem are we trying to solve?)

- The desired level of participation (how much do we want to participate? How far do we want to go in terms of participatory democracy?)

- The scope of participation (In what kind of activities people are participating? What do they participate with?)

- The possible outcomes of these participatory approaches on existing power dynamics (how do these participatory approaches re-question the way we make cities?)

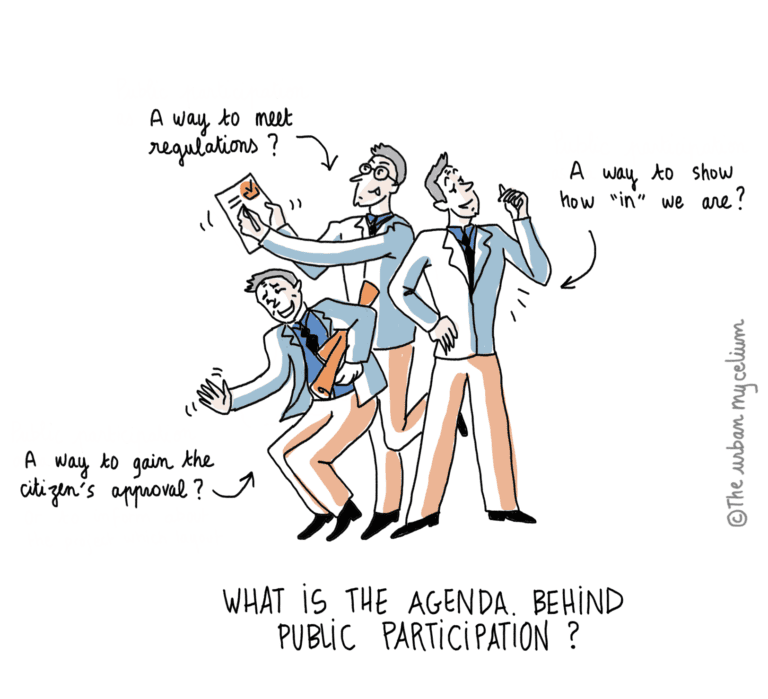

To me, this is all quite natural, as we usually tend to focus on the concrete and tangible things. In an urban project, this may be the urban plan, the layout of the apartments, or the landscape architecture, to name a few. Everything that Simon Sinek refers to as the what in his famous “golden circle”. According to him, we focus most of our attention on the what, and less on the how, which in our case would be for example the budget, timeline, number of collaborative workshops, project management process, and so on. And more importantly, we virtually never focus our attention on the core question, which is why we do what we do. Why do we really need this participatory approach, for what deep intention? Why do we even build here?

The Ladder of Citizen Participation

In reality, participation can serve different objectives, and it is essential that the project team (decision makers and designers) agree on this before they start to involve citizens. The risk otherwise is to disappoint people, generate frustration, or simply waste time and (often public) money.

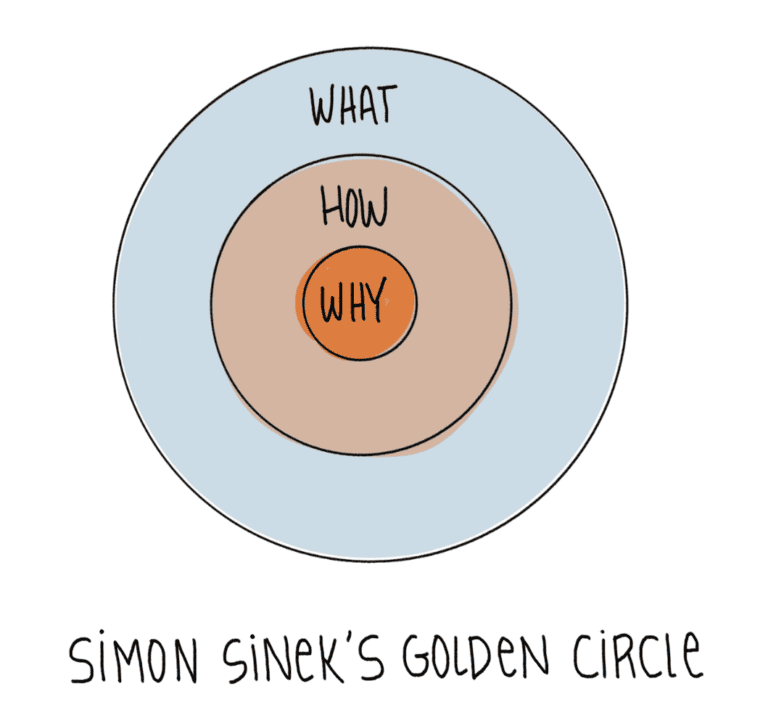

Regarding participation in urban planning, Sherry Arnstein (1969) defined eight different levels to identify the actual power of citizens. Called “The Ladder of Citizen Participation”, the model has different steps which move bottom to top, from non-participation to symbolic participation (counterfeit power) to degrees of citizen participation (actual power).

Of course, like any model, the ladder has its own limits. First of all, it is metaphorically represented as a ladder, implying that the more you move up, the better. In reality, the lower levels shouldn’t be interpreted as universally negative, and vice versa. For example, it is sometimes completely appropriate to rely on information only. And in other times, there is no added value in involving citizens in each and every decision taken – and that is OK. Adding to this, the ladder has steps which can each be interpreted as final (once you’re there, you don’t move). In real-world participatory situations, there are a lot of fluctuating dynamics, some of which are not even predictable. As a matter of fact, people may move up and down the ladder over time, within the same project.

Broadly speaking, though, the ladder is useful for interpreting what is meant when policies refer to “participation”. It should be reminded that it is only in recent years that participatory approaches started to be used by public institutions and integrated in programmes and policies. Before that, power was usually not voluntarily shared by decision makers but rather taken by the citizens through activism or bottom-up community organizing.

And so, what the ladder of citizen participation means, is that as long as the purpose of participation is not clear, there will be greater chances to stay in what Arnstein calls “tokenism”: doing something only to show that regulations are being respected, or doing what is publicly expected (and not because you really believe it is the right thing to do). In other words, as long as there is no serious discussion about the why, public participation will remain the icing on the cake: a “nice extra thing” in the urban project, next to the technical studies.

In reality, I believe that participatory processes are transformative journeys, in which power holders and the less powerful are partnering to take decisions and actions. When done well, these processes can install new ways of working that may deeply affect all facets of the project and question the existing status quo. For now, I believe that the gap is huge between what public participation is perceived to be, and what it actually is (and what it can do). It seems to me that the actors at the top are not aware of how much they are going to move, personally and professionally, as a result of working differently.

Towards a deeper discussion about the politics of participation

This is exactly why we need to discuss more in depth the political agenda behind public participation in urban projects. It is important to clarify the expectations of the stakeholders who launch these programmes and genuinely explore how these new ways of working are questioning existing power dynamics. When properly carried out, these collaborative processes can in fact create a firepower of questions around democracy, which can in turn destabilize policy makers, if they are not prepared for it. The power holders who are responsible for such processes should know what kind of journey lies ahead of them.

Therefore, in the early stages of a project that involves citizen participation, it can only be helpful to spend some time on clarifying why we really want participation, what we want to participate about, and how far we want to go in terms of partnership.

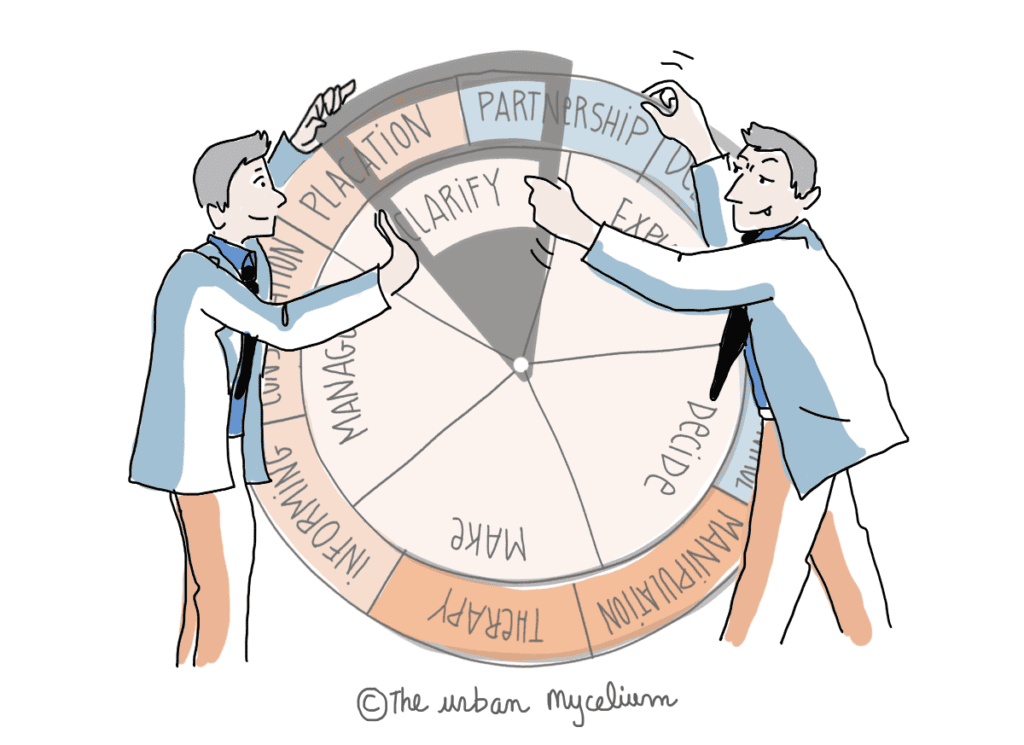

To help with that discussion, I personally use the model of a wheel, which avoids a hierarchical interpretation and guides the project team along 2 different layers of objectives for public participation:

- The 5 objectives of the participation regarding the urban project: what do we want to achieve with people on that specific project? What is the aim of including them, here and now?

- Understand and clarify: conducting a diagnosis of the existing situation (urban form, uses, current place management…) and clarifying what the problem is, understanding the perception of the users

- Explore: identifying creative solutions as an answer to the identified problems; identifying a shared inspiring vision for the future of the place, enriching an existing urban scenario

- Decide and orientate: setting up criteria and choosing the first actions to launch, validating with all the concerned actors

- Make: setting up the concrete actions in space, use or organization, building things, funding projects

- Manage: monitoring the space and taking care of it over the long-term including maintenance, funding, place management, governance…

- The levels of partnership between the power holders and citizens, as defined by Arnstein (1969):

- Manipulation: biased information used to educate citizens by giving them the illusion that they are involved in the process. The aim is to achieve public approbation;

- Therapy: superficial treatment of the problems encountered by the inhabitants, without addressing the real core issues. The aim is to achieve public approbation;

- Information: citizens receive real information on current projects, but cannot give their opinion (one way flow);

- Consultation: surveys or public meetings allowing citizen to express their opinions on the urban project, but without any guarantee that their opinion will be taken into account;

- Placation: hand-picked citizens are allowed into debates or committees, to advise and influence the implementation of projects. The power holders are still the ones to judge the legitimacy and feasibility of the advice;

- Partnership: power is redistributed between citizens and power holders through negotiation. Planning, decision-making and action are done through real collaboration and co-creation;

- Delegated Power: power holders give up at least some degree of control, management, decision-making authority, or funding to citizens;

- Citizen control: citizens handle the entire job of planning, deciding and managing a programme, for example a local community managing a facility or neighbourhood with no intermediaries.

How to use the wheel of participation?

Who should use this wheel?

This will be especially useful for the stakeholders such as municipalities, building operators, urban planners, designers who would like to launch a participatory process to city making. It is important to engage the decision makers in this process, as it will lead to strategic discussions on the politics of participation. Also consider bringing in a facilitator to help frame and guide the discussion. Foster an atmosphere of trust and transparency.

How to use the wheel?

- Start by having a discussion around public participation in general, its benefits, challenges, risks, and why it is important for each stakeholder

- Then go through all objectives and types of participation. Make sure everyone understands, maybe by giving examples that have been carried out in the city or elsewhere

- Write down the core intention, or the problem that we are trying to solve with participation, and make sure everyone understands it. Pay attention to generic sentences such as “it will bring more conviviality” and try to be as precise as possible

- Base statements on facts and knowledge. Distinguish causes from symptoms. One can also use the 5 Whys technique which consists in identifying the root cause of a problem or intention by repeating the question “Why?” 5 times.

Yes, it takes some effort to raise and address these questions on citizen participation. I understand that it can be frustrating to spend time on this, when all one wants is to take action. However, there is a great chance that bringing attention to this topic will in turn lead to a beautiful discussion between the city stakeholders and a clearer understanding of the politics of participation.

Arnstein, S. (1969.) A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Planning Association, 35(4), 216–224.