When I was 12 years old, my family and I visited my aunt and uncle in the United States during the summer holidays. We rented cars and visited lots of great places, thanks to my aunt who had nicely planned the whole itinerary. However, not everything went as planned.

One night, as we were driving back to Las Vegas after an exhausting day in Death Valley, we got lost. About 15 minutes before arrival, my dad, who was following my uncle on the highway, suddenly missed the exit to their neighbourhood. First, we thought it was not a big deal and we were planning to take the next exit and loop back. It was trickier than that, though, and before we even realized it, we were completely lost in Las Vegas, wandering around neighbourhoods with look-alike streets and houses.

There was no GPS in our rental car back then, and we actually didn’t know the exact address – the only thing we remembered was that there was a Target store at the corner of their street. So, from time to time, one of us would frantically point at a Target and scream that they recognized it. Our disappointment was great, when we realized that the whole area counted dozens of similar Targets at the corners of streets. Adding to this, and to spice things up a little, we couldn’t reach my uncle and aunt… as their phone was in our car.

I spare you the angry screams, crying children, hunger, and desperate encounters with bystanders in our broken English. Eventually, we attracted the sympathy (or the pity) of a bartender who was nice enough to guide us and provide us with the right itinerary. I will forever remember the relief in my aunt’s eyes, as we parked in their street. The funniest part of this all is that they were still standing outside, because the key to their house was… in our car!

Why do I share this story, you might wonder?

Following this misadventure, I must say that I often wondered why it had been so hard to find our way that night. Why were even my parents unable to make sense of their environment, although they knew their way around? I never got a satisfying answer, until years later, when I followed classes in environmental psychology as part of my urbanism studies. I learned about cognitive mapping, and suddenly, everything made sense. Now you maybe see where I’m going…

A cognitive map is a mental image that people have of a large-scale environment. Cognitive mapping is very important, because it is the foundation for human wayfinding. Based on cognitive maps, people can process information, move from place to place, and eventually find their way around.

How do we develop wayfinding?

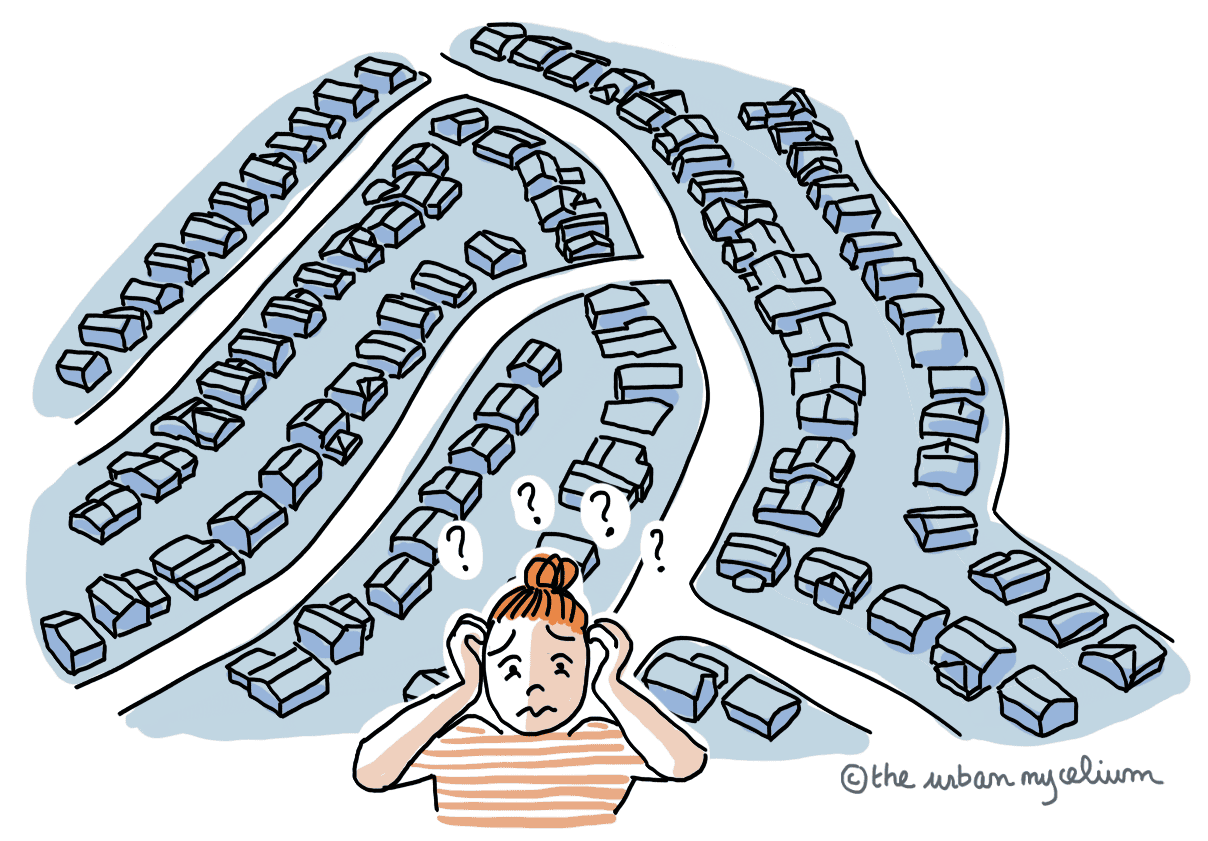

We don’t make cognitive maps overnight. There are developmental theories that describe the stages in which children, or adults in new environments, develop cognitive maps. It actually follows different steps:

- Landmarks: First, children tend to remember landmarks or objects which are easily recognizable (even from one specific side) and can be recalled from memory according to the street setting. In this first stage, children map their environment by associating landmarks together.

- Route map: Next, children start to map their neighbourhood as a large network of routes linking objects together. With time and experience, the routes are not drawn only from landmark to landmark, but rather from place to place where we experience something new or have to change direction.

- Survey map: Finally, children start to create global maps of large-scale environments where landmarks are separated by greater distances. The brain knows what is not visible, and makes predictions to know what direction to take. It comes with time, experience and human prediction.

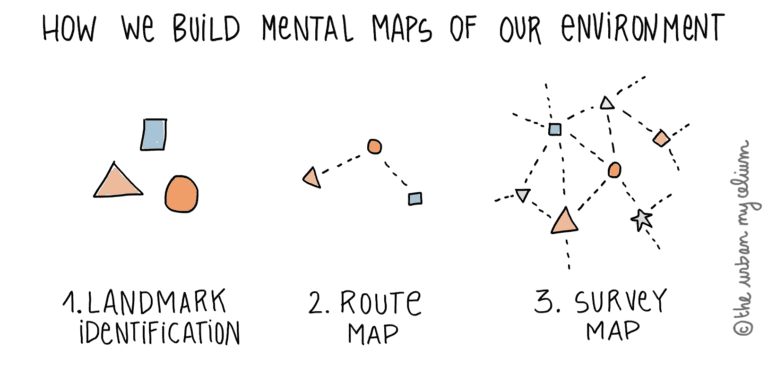

What we call “landmarks” here is not necessarily a century-old church. It can be a less significant object, for example a lamp post, a shop or a tree with a very particular shape. Although landmarks are the elements that probably stand out the most, there are other elements that people remember in the city which contribute to creating and maintaining cognitive maps. In The Image of the City, Lynch actually lists four more elements: paths, edges, nodes and districts.

At the end of the day, people will eventually always make sense of their environment and find their way. However, wayfinding problems can occur in urban environments that have repetitive layouts and a lack of clarity. The typical American suburb that I pictured earlier is an example of an urban environment where wayfinding may be hard, even for individuals who have acquired a solid cognitive map of their environment. So, how can we make wayfinding easier?

Design recommendations for effective wayfinding

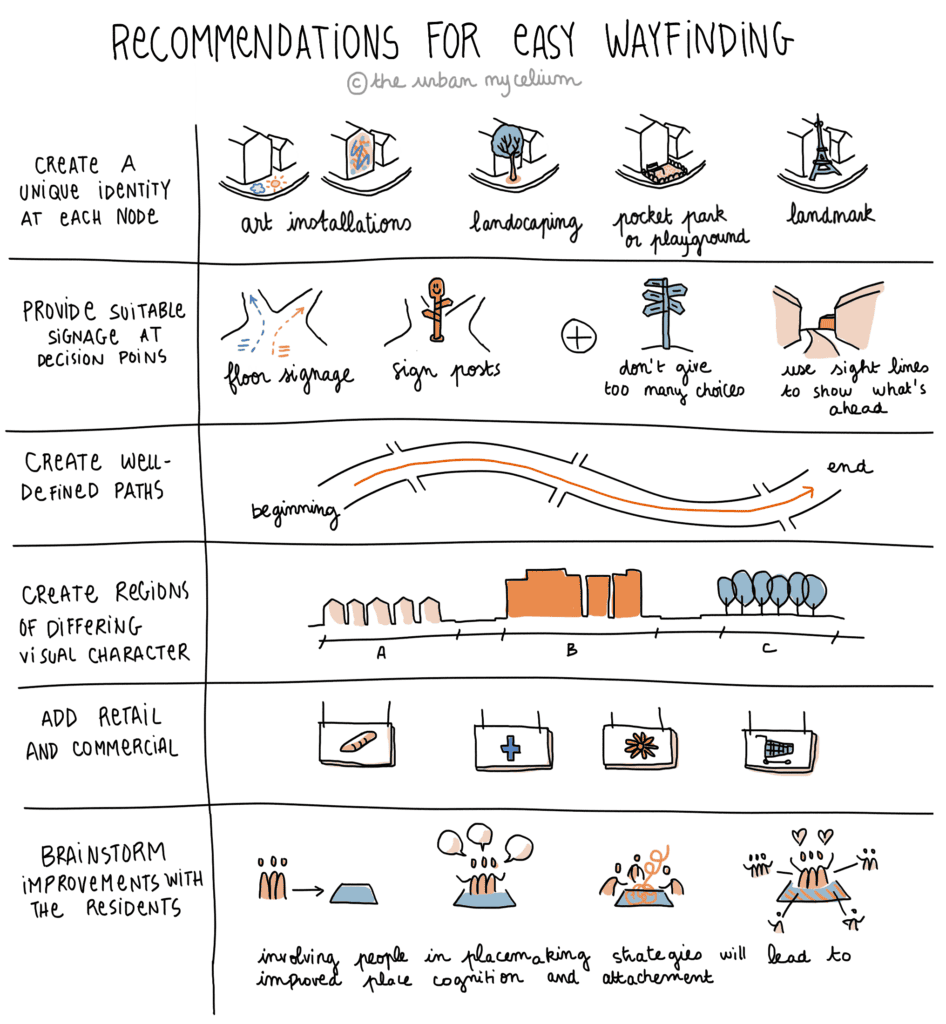

Design principles for effective wayfinding include the following:

- Create an identity at each location, different from all others

- Use landmarks to provide orientation cues and memorable locations

- Create well-structured paths

- Create regions of differing visual character

- Don’t give the user too many choices in navigation

- Provide suitable signage at decision points to help wayfinding decisions

- Use sight lines to show what’s ahead

But we can’t solve everything with urban design only. Actually, there seems to be a gap between how urban planners and designers see the city and how it is perceived by the non-practitioners. In her research on suburban navigation, Klasander asked people living in different suburbs of Göteborg (Sweden) what they noticed in the urban environment. She wanted to highlight properties that would support wayfinding. Most often, people did not recall places based on their physical attributes such as colour, height or materials; instead, they remembered the function of the buildings only, or its shape as an edge (ex: the building on the corner of the street). This is exactly what happened to us in Las Vegas, when we tried to find our way based on the memory of a neighbouring Target store.

Beyond spatial principles, I would therefore add the 3 following recommendations:

- Add commercial and retail to break up residential continuity, because people tend to remember buildings by their function rather than by their physical attributes;

- Involve the local community in placemaking strategies and brainstorm improvements with the residents. This will lead to increased place cognition and attachment;

- Create better planning documents to promote architectural and functional diversity in design (documents that are informed by knowledge on cognitive mapping).

These principles for effective wayfinding are summarized in the following table.

Understanding the theory behind cognitive mapping is important to improve wayfinding in urban environments that lack definition and differentiation. Quite interestingly, what designers mostly focus on, that is architectural, urban and landscape design, is not necessarily what people will remember when they try to make their way around. This very point demonstrates the importance for urban practitioners to understand human behaviour in order to design better places.

Chown, E., Kaplan, S., & Kortenkamp, D. (1995). Prototypes, location, and associative networks (PLAN): Towards a unified theory of cognitive mapping. Cognitive Science, 19(1), 1-51.

Foltz, M. (1998). Designing Navigable Information Spaces. Master of Science. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Gärling, et al. (1986). Spatial orientation and wayfinding in the designed environment. A conceptual analysis and some suggestions for postoccupancy evaluation, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Volume 3, Number 1, 1986, p. 55-64.

Klasander, A.-J. (2004). Suburban Navigation: Structural Coherence and Visual Appearance in Urban Design. Doctoral Thesis. (Gothenburg: Chalmers).

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. 1st ed. The MIT Press.