Have you ever wondered why some city spaces are working out well for people, and others are not? Why do some spaces, and even newly designed ones, remain empty most of the time? What makes a good public space for people?

These are some of the questions that American urbanist, journalist and sociologist William H. Whyte (1917 – 1999) asked himself, back in the New York of the 70s.

Dedicated to find answers, he formed a small research group in 1970 while working for the New York City Planning Commission, with the objective to investigate the human dynamics in different urban settings. This was called the Street Life Project.

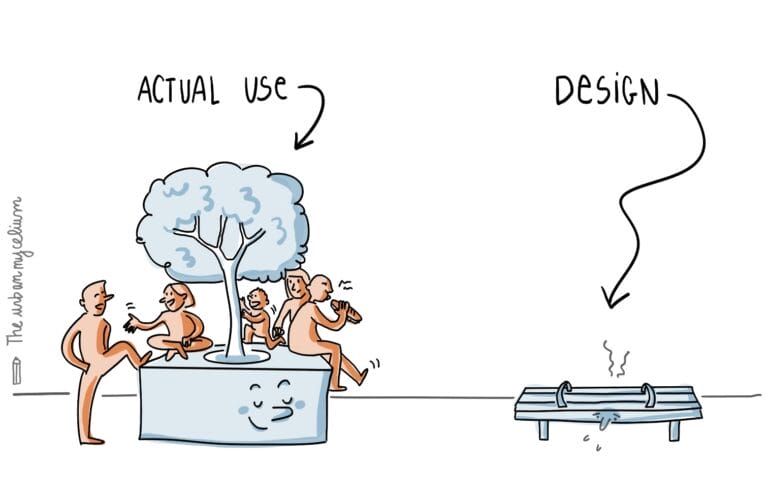

Whyte was convinced that there is a lot to learn from simply observing spaces and the people using them. Using time-lapse cameras and direct observation, he and his team recorded daily patterns and pedestrians’ behaviours in a dozen of different parks, plazas and other informal recreational areas. Their observation took place at different times of day and with different weather conditions. They were looking at the following things:

- What are people doing in public spaces? What are their rituals, their habits?

- Are they alone or in groups? How do they greet, how do they say goodbye?

- Where do they choose to stand, or to sit?

- How do they move around? Where are they coming from, where are they going?

In 1980, after 10 years of research, the team’s findings were finally collected in a book called The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces and synthesized in a companion film, which is full of interesting insights on the lively dynamics of public space (or what Jane Jacobs would call the “sidewalk ballet”).

The key ingredients for a good public space

Now, you might wonder if Whyte and his research team found what makes public spaces good for people. Well, they did, and most of their findings are remarkably simple.

Generally, they found that good public spaces had many people in them, and that “what attracts people most it would appear, is other people”. Good places have both people in groups and people alone, people reading, talking, playing, eating, observing each other, demonstrating affection, walking, shopping, etc.

But beyond other people, people also do like some basic elements in public space, which are summarized in the visual below.

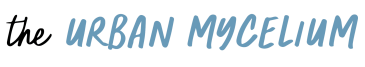

All of this knowledge sounds obvious? It is! However, we keep missing it and even many newly designed public spaces still lack these basic elements.

So, what made William H. Whyte’s approach so pioneering?

Apart from his common-sense principles, Whyte definitively had a pioneering approach.

- Observation is key

More than a theoretical background or aesthetics about city spaces, Whyte believed that planners and designers can learn a lot about what people want in public spaces, if only they “look hard, with a clean, clear mind, and then look again – and believe what [they] see”.

Today, many urban practitioners rely on these street observation / analysis tools, but at the time, it was completely ground-breaking. Sociological and field-based studies had been carried out in other fields, but it was unprecedented in urban planning.

It is also through simple observation that Whyte came to counterintuitive insights, such as this one about the so-called “undesirables”: instead of fencing places off and designing unfriendly urban furniture that will eventually chase everyone away, Whyte suggested that we should rather make places as welcoming and attractive as possible.

So, Whyte’s invitation is to leave our assumptions behind and to go down at the street level so that we see what people need and want with our very own eyes. An approach which is widely advocated today by the Placemaking movement or The City at Eye Level.

- It doesn’t have to be grandiose

For people to enjoy public spaces, we saw that it goes down to a few basic, simple elements. It doesn’t need to be fancy. People will not use spaces that do not feel comfortable for them, however grandiose they are. With his humble approach to urban planning, William H. Whyte gently reminds us that the magic happens in the ordinary…

- Bottom-up design

Based on the observation that people were using places that were comfortable and convenient to use, and simply discarding the ones that were not, Whyte strongly encouraged a new way of designing places from the bottom up (and not the other way around).

- “Triangulation”

Whyte used this word to refer to “the process by which some external stimulus provides a linkage between people and prompts strangers to talk to other strangers as if they knew each other”. When placed in relation to each other, different uses, services and space elements can lead to new encounters and human dynamics that can activate the space.

In other words, for a place to attract people successfully, there should be at least a few reasons for people to come there (food, sitting choices, an open window to an activity, music, art sculptures, water…). Something which Project for Public Spaces refers to as “the Power of 10”.

William H. Whyte has greatly influenced the way we approach urban planning and design. Together with other inspiring figures like Jane Jacobs, they have laid the foundations for the growing placemaking movement that is thriving today: a movement in which we make cities not only for people, but with them.

Whyte, W. H., 1980. The social life of small urban spaces.