As we saw in this article, public participation is not for everyone, as it often attracts the same profiles again and again, and fails at involving people whose voice is heard the least. Is it possible to escape this recurring pattern? Should everyone really participate? Who is everyone, at the end of the day?

In reality, there is little discussion about who exactly should participate in participatory processes, and why. This is an essential question, though. Just like it is important to clarify the objectives of public participation, it is also important to talk with the power holders about who should participate in the process and why, before the launch of a participatory project.

To do so, there is nothing better than to break down some mental beliefs we might have about the participants of public participation. Let’s go!

There is no such thing as “the residents”

New programmes that require public participation often advocate for the involvement of “the residents”. It may be for example the residents of an existing building which undergoes renovations, the neighbours of a soon-to-be built building, or the future inhabitants of a neighbourhood under construction. The residents are very important to consider, as the people who live, or will live in these places.

However, it is usually vague which kind of residents we are talking about. In fact, “the residents” is not a homogeneous group consisting of identical individuals. They actually have different stories, needs, problems, and dreams…

Within “the residents”, you can find young people, older people, people with jobs, others who are unemployed, people working at night, students, people with kids, people without kids, recomposed families and single mums, people freshly arrived in the neighbourhood, some who have lived there for ages, etc. And of course, each of these categories can also be divided into subcategories, the group “the elderly” for example consisting of very different profiles of elderly people.

It is important to go beyond these generic categories and to understand more precisely who are the people who live and use the space, in order to design a place with a real singularity. Observing on site, analysing demographic data, or conducting interviews are examples of things that can be done to better understand the residents.

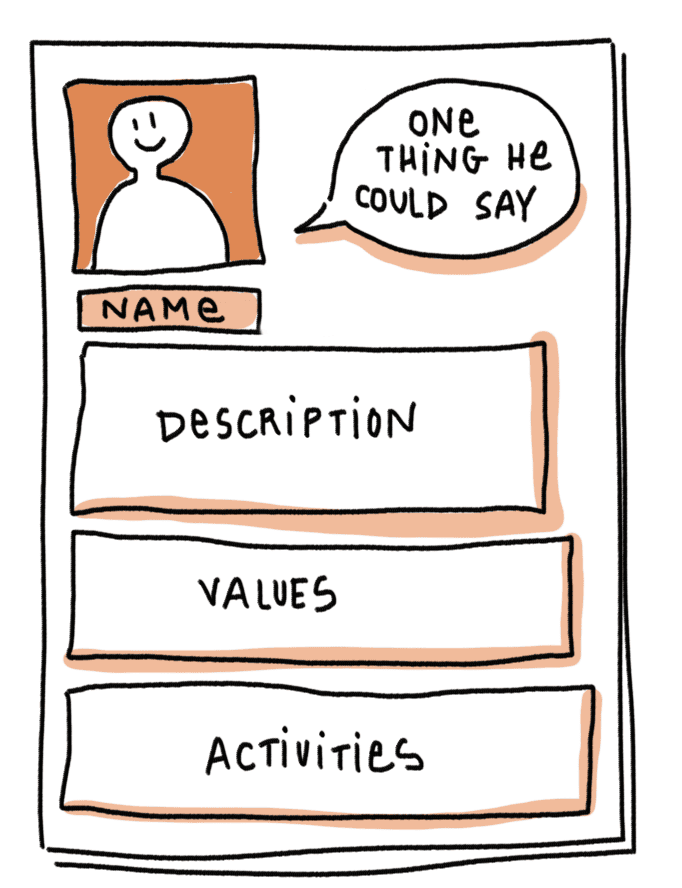

Following that, it may be useful to design “personae” or archetypes that represent a group of people with similar behaviours, motivations and goals. For a specific urban project, one persona could be “seniors above 80 who have lived in this building for more than 20 years”, or “families of young children under 10 who are using the local school”. Creating personae is not about labelling people – one person can actually match different personae, depending on the context. Instead, it is about understanding the sociology of the place in order to design appropriate solutions that match people’s real needs.

You can find plenty of templates online for personae design, but here is one example:

The residents are not the only ones to consider

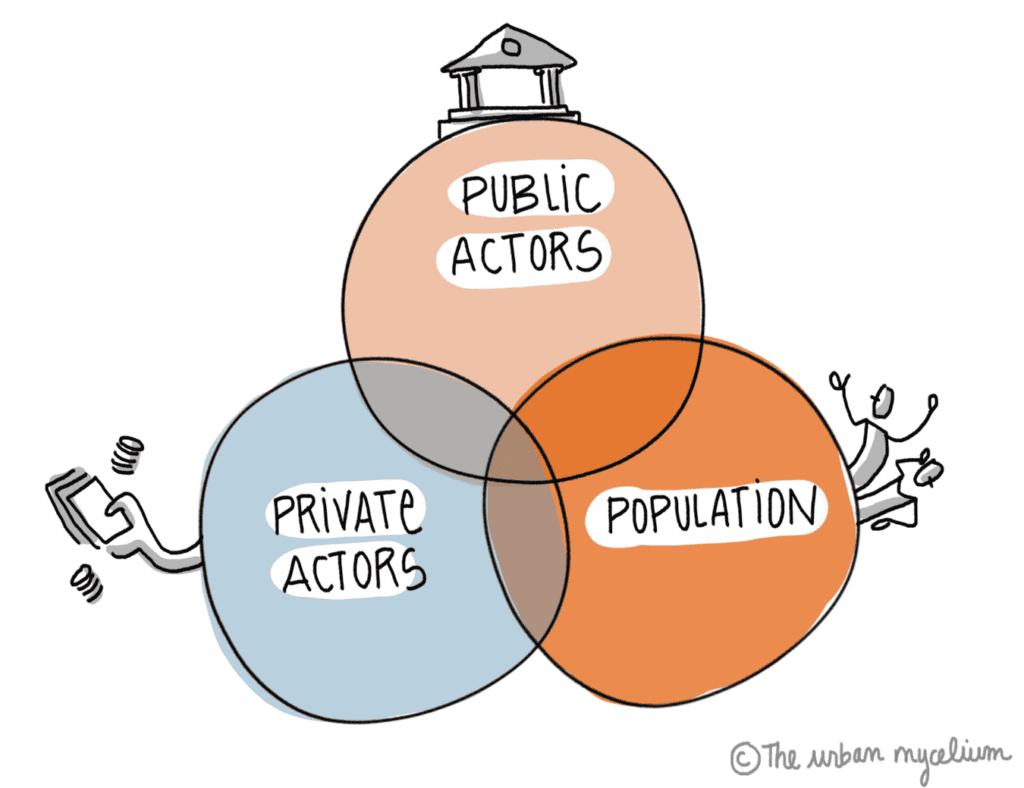

With that being said, there are many more stakeholders to consider than just the residents. Different models exist for stakeholder analysis, but an easy and very mnemotechnic one is the following PPP model, that accounts for Population, Public, and Private actors.

- Public Actors: municipalities, regional and governmental bodies, other public institutions in the field of planning, the environment, health, culture and sports, resource management, funding, etc., as well as schools and universities;

- Private Actors: local entrepreneurs, companies and retail shops, urban practitioners (designers, engineers, planners…);

- Population: residents, neighbours, everyday users of the space, local associations and other non-for-profit groups.

Mapping the local stakeholders is the best way to fully understand the context of the urban project. This can also lead to sustainable partnerships between public, private and civic actors, already from the planning phase. Especially with the private sector, which is usually left aside in participatory processes. Even when they are invited, local companies and entrepreneurs will most likely not attend public workshops in the evenings, because of business hours or other running projects.

Meeting them (on their own agenda) is very important, though. For example, a bakery which is just 300m away from a new neighbourhood will greatly benefit from the arrival of new inhabitants. On the other way, future residents will surely enjoy getting their fresh loaf of bread just close by. From there, new services can be imagined that will benefit both the business and the citizens (a delivery service provided by the bakery or a bread dispenser in the new neighbourhood, for example). This leads to win-win partnerships!

Not everyone should participate in everything

We talked about how public participation processes were not always inclusive, and we mentioned a few ways to address that. But even before that, comes the question of the proximity to the urban project. If the empty lot next to your apartment block is going to be turned into a new residential neighbourhood, wouldn’t you like to be given a little bit more priority than people who live at the other side of the city?

So, one thing we might want to do it to focus first on the people who have a close relationship to the urban project. People who live close by, people who use the space often, people who may be concerned or impacted by the project in another way, or those who simply wish to be informed.

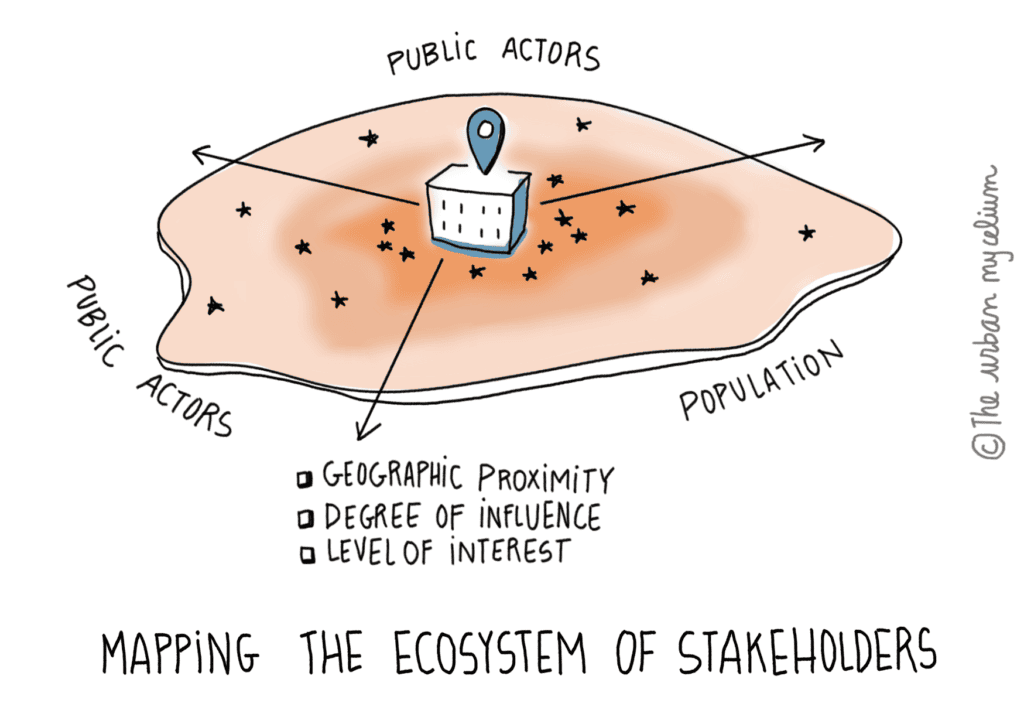

And this actually goes together with understanding the objectives of the project and of public participation. On the following figure, local stakeholders (should they be public, private or citizen actors) are mapped based on their proximity to the urban project.

It is important to map the local stakeholders with care, and to identify who should participate, and why, based on geography, degree of influence and interest, and representativity.

With that being said, I personally think that not everyone should participate in everything. This may be hard to understand for municipalities that are supposed to treat everybody in the same way, but unfortunately, it is unlikely that everyone will participate in everything. As one of the principles of the Open Space Technology says: “whoever comes is the right people”. Should they be 2 or 10, 50 or 200… the motivated few who will take the time to join and discuss the future of cities, are the right people!