In the traditional practices of urbanism, the power has always been held by the same actors. The making of the city has long been a closed technical and political discipline reserved to “experts” only. Excluded from this process, citizens were unable to voice their points of view and visions in an official way.

Participatory practices in urbanism tend to rebalance these power relationships, in order to benefit those whose voice is heard the least. Adding to this, they offer great potential to positively transform the urban environment, together with the different stakeholders. But what are we talking about? What does it mean, to make the city together? What are the benefits of participatory practices, for the citizens and for the professionals of the city?

The benefits of participatory practices in urbanism

There are many reasons why the making of the city should no longer be the business of the experts only.

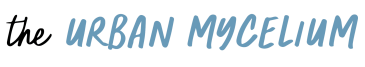

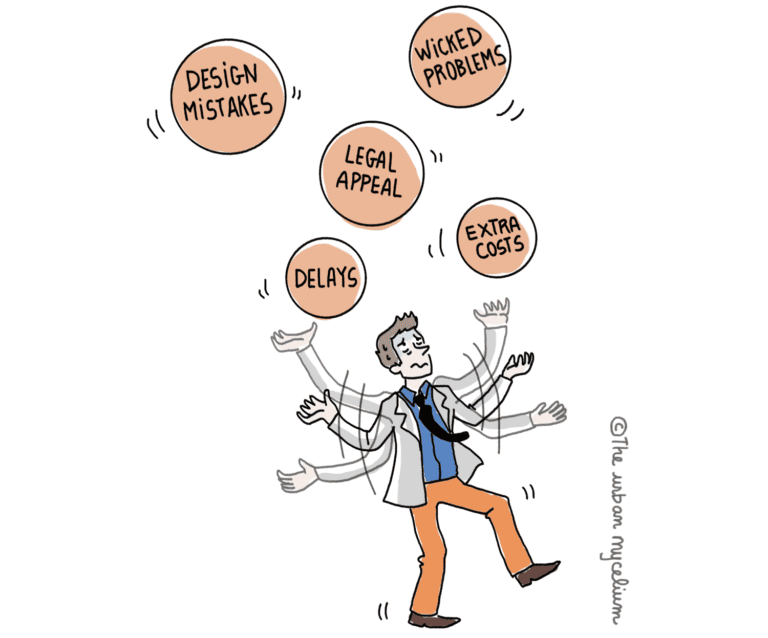

- First of all, as we have seen previously, cities are faced with “wicked problems” which require the intelligence of many different stakeholders, beyond the mere urban “experts”;

- Secondly, it is not rare that brand new buildings or neighbourhoods, once they are delivered and used by the inhabitants, show defects or poor design that could have easily been anticipated with the input of the everyday users;

- Thirdly, when the power holders present their urban plan in public meetings, they often must face the concerns and objections of the citizens – sometimes with uncomfortable confrontations that end up in legal appeals and extra delays;

- Finally, the combination of all of the above and a history of conventional urbanism that systematically excludes the non-professionals of the city has resulted in a strong lack of trust in the local authorities and urban experts.

This is a lot to handle! Participatory practices in urbanism provide concrete solutions to these recurring problems and ease the burden of the experts’ responsibilities. Creighton (1994) has listed the following benefits:

- Improved quality of decisions

- Minimizing cost and delay

- Consensus building

- Increased ease of implementation

- Avoiding worst-case confrontations

- Maintaining credibility and legitimacy

- Anticipating public concerns and attitudes

- Developing civil society

To this existing list, I would also add the following:

- Developing soft skills, such as empathy, active listening and problem analysis

- Generating new, creative ideas and partnerships to enrich the urban project. Integrating different points of view, not through compromise, but by exploring the creative potential of conflicts, leads to innovative urban solutions.

Generating opportunities for public participation is very important in city making. Not only can designers and planners benefit from getting the opinions and experiences of the people who use the urban spaces every day, but the citizens themselves can take a more active role in the modification of their own environment.

The citizens’ right to making the city

The rise of such participatory practices in urbanism actually echoes the discussions in academia about “the right to the city”. In fact, some voices such as Harvey (2008) argue that it is the citizens’ right and responsibility to collectively transform their environment and reshape urban processes.

There are many ways to take this right back, mostly through bottom-up initiatives and grassroot activism that try to reclaim public space. It is not such a long time ago that “public participation” actually became a legal requirement in France, embedded in conventional urban development programs.

However, allowing people to express their “right to the city” is easier said than done. How to do that? Which role should they take next to the experts? Empowering citizens and enabling them to transform their urban environment in fact requires a whole new mindset and way of working.

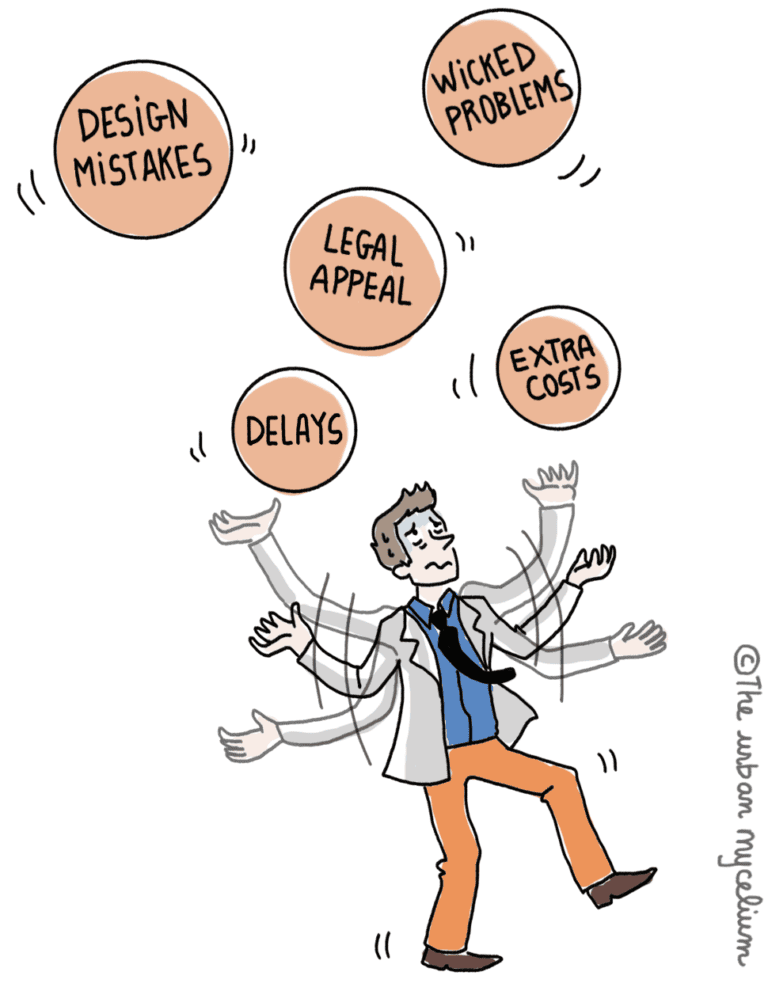

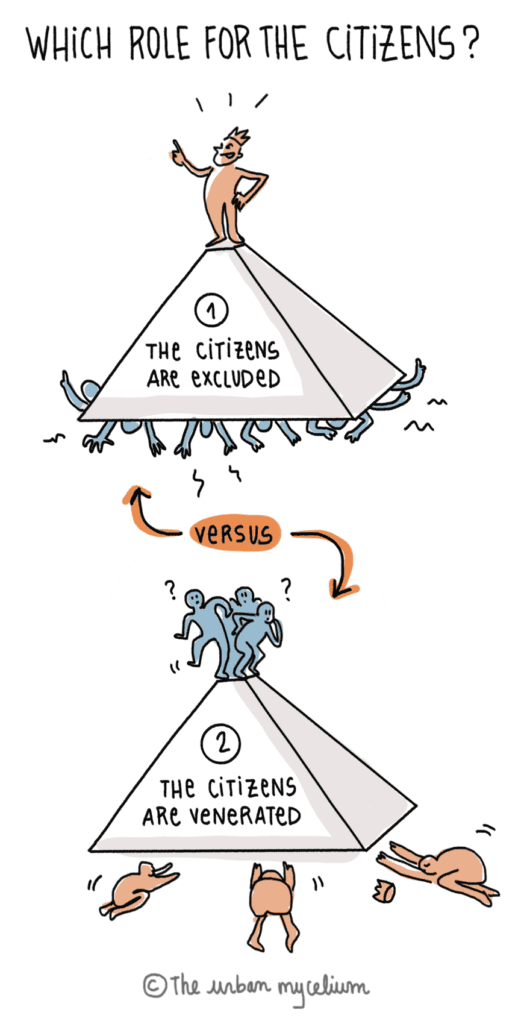

Throughout my experience in public participation processes, I have sometimes noticed from the power holders a form of “praise” for the citizens. In a matter of years, citizens simply went from not being included at all, to being placed on a pedestal. Which basically consists in reversing the pyramid, without really questioning the power relationships that lay behind.

Giving people back their right to the city is not about that, I believe. It is not about relegating the entire responsibility to the citizens, because the power holders are unwilling or unable to assume it any longer. Rather, it is about giving citizens the right to question the power holders’ role and responsibility in the making of the city.

In a process of genuinely making the city with people, and not only for them (read: in their place), citizens are neither spectators, nor dictators of the future of places. They are experts of the urban life, worthy of standing on the same stage as other stakeholders involved in city making.

Because yes, the residents and users of the city have a certain experience and knowledge of the places they inhabit. An experience which is different, and complementary to the one of urban experts and decision makers. Listening to people and understanding their concerns will lead to improved design solutions that really match the needs of the community. People will feel relieved, when they are listened to; and experts will find it much more fulfilling to design an environment that matches the future users’ expectations. Eventually, it will generate more trust between the different stakeholders.

On the following figure, the different stakeholders: residents and users, associations, local entrepreneurs and public institutions, authorities and administrators, urban planners and designers are all integrated in the process as equal partners. It is not only the citizens who must “change themselves by changing the city”, as stated by Harvey (2008), but also the local authorities and experts who conduct the urban development programs. In this context, the professionals are no longer in a central role of providing solutions, but rather enablers of change, next to the other actors.

Everyone in the group, professionals and non-professionals alike, have a set of skills and stories that go beyond their mere professional title. When combined, these individual strengths and personal experiences become very powerful and can feed a common discussion, a common goal. The collective then goes much further together than when thinking individually!

Creighton, J. L. (1994). Involving Citizens in Community Decisions Making: A Guidebook. Washington, DC: Program for Community Problem Solving.

Harvey, D. (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review, October. Issue 53.